Audio Basics for Hams, Part 3 – Signal Chain

If you’ve read through the first two installments, you’re pretty much an expert in microphones now 🙂 . I think it’s time to move up the audio path a little bit and start getting into ways you can route and process your audio. There’s a good bit to this, so no doubt it will take a few more posts to get through it all, but I feel confident that it will be worth it in the long run. And please keep in mind that this is called “Audio Basics” so I don’t intend on going into all of the nitty-gritty details that more advanced engineers might like. Sorry!

A microphone needs to plug into something, right? If you’re anything like me, you love wires and cables, so you need to make sure that you get yourself at least a few good XLR cables, which are the standard when it comes to connecting your beloved mic to your other audio gear. XLR cables are round, have both male and female ends, and normally have three conductors to provide a balanced connection (keep in mind that the terms balanced and unbalanced have slightly different, albeit analogous meanings in audio than they do in terms of antenna types). That’s a term that will be important for you to know: balanced connections require three conductors to operate and are very good at rejecting noise that could be induced by nearby RF fields, especially in long cable runs. They do this by using a number of different methods, and if you really want to know what those are, you can read the Wikipedia article relating to balanced and unbalanced lines here. Balanced lines differ from unbalanced lines in the fact that unbalanced cables, like your typical home stereo RCA cables, usually have only two conductors (one for shield/ground and one for the signal), where balanced lines have three (+ signal, – signal, and shield/ground). Unbalanced lines are fine for short runs but can also introduce noise if they’re positioned near noisy power supplies or other leaky gear. You can buy BalUns for audio gear, but those usually also alter the impedance between the two lines also. We won’t get into that now. One other thing: XLR connectors are not the only balanced ones; any TRS (tip-ring-sleeve) connectors, like the ubiquitous 1/4″ TRS, can also be balanced depending on the setup, and there are other types also.

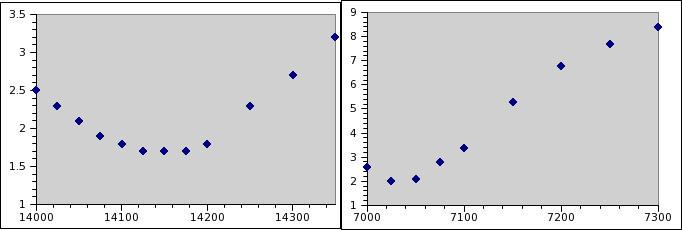

So now you have a mic and a cable and you want to do something with it. Let’s explore one more concept before we get to the final piece of gear for this post: the difference between microphone level signals and line level signals. If you remember way back to the first post, we discovered that microphones output very little voltage regardless of whether they’re dynamic or condenser mics. It’s on the order of 5 to 50 millivolts, depending on the mic. That voltage is far too low to be usable in most gear which typically operates at line level which is on the order of .3 to 2 volts. To complicate things further, there are different “line level” voltages depending on whether you’re talking about professional or consumer level gear, but that’s better left to be explained by Wikipedia if you’re still interested. All of this is to say that we somehow need to get our wimpy mic level signal boosted up to a line level signal if we want to be able to use it with the rest of our stuff. This is where a preamp comes in.

You can probably guess that the term preamp is really just short for preamplifier. Big deal. The big deal is that this amplifier is probably the most important one in your signal chain, so it’s good to get it right. If we start to introduce noise into the audio at this point, it’ll just get worse as we go along. Now this probably isn’t as big of a deal to hams as it would be to someone in a recording studio in Nashville, but it’s still a good idea to make sure that you have a decent preamp if you intend on using an external mic with your rig. Preamps come in all shapes and sizes, from expensive external 1U rack-mounted vacuum tube models, to small, desktop units, and even to the ones that are built into and part of an external audio mixer. They all do pretty much the same thing: amplify your mic level signal and turn it into a line level signal that’s easier to use with the rest of your gear. You can take a look at all of the pretty external audio preamps here. Some are cheap ($50) and some are expensive ($thousands!), but to some degree, you do get what you pay for.

So finally for this post: how should you choose a preamp, or do you even need one? Well, there are a few other things that need to be considered, but the main question is how you plan on using it. You might not need an external preamp if you intend on connecting your new dynamic mic directly to your rig- your radio probably already has a sufficient preamp built into it. If you want to use a condenser mic with your radio, though, you’ll at least need a device to supply phantom power, which most preamps can do by default. You’ll also want an external preamp if you intend on processing your audio with any other external gear before it makes it into your radio because that will all want your signal to be at line level. If you are thinking about concentrating all of your audio routing into one place, it might make good sense to get an audio mixer that has preamps built in. We’ll talk about audio mixers next time.

Hopefully you’re starting to be able to see a larger part of the picture as we progress. It might seem tedious, but it’s really important to understand the fundamentals very well before you start putting things together to make sure that you don’t get in a bind down the road. We all want happy hams!

And now that you know how to plug stuff up and what a preamp does, it’s the perfect time to go learn a little about audio mixers: Audio Basics for Hams, Part 4 – Signal Routing.

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.